Walker on Stunt

Paul Walker prepares his 2015 Predator for a flight on the way to his 12th victory in Precision Aerobatics at the U.S. National Championships. Bob Hunt photo.

You have the chart -- Now to the trimming process!

By Paul Walker

December 2015

(EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the seventh installment of Paul's most recent trim flow chart update and series of articles. These articles were first published in Stunt News, the magazine of the Precision Aerobatics Model Pilots Association, and are reprinted here by permission of SN editor Bob Hunt.)

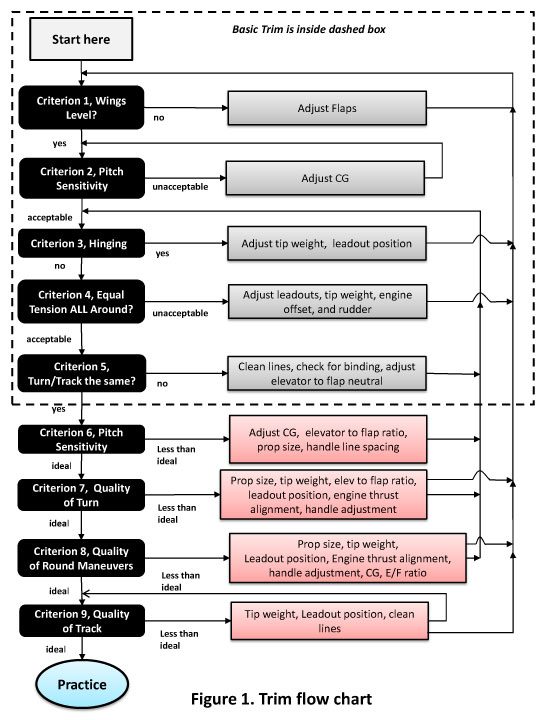

With the last installment, we finished the tour through the trim flow chart. This gives you a process to attack the trim adjustments on your killer machine! However, there are a LOT of variables to cover if you want to be thorough. This time we will discuss ways to shortcut some of this process, and general observations I have made through the years. This is all to help you streamline the trimming process.

Let's start with observations. Here is a list of several common issues I see with many CLPA pilots.

- People tend to fly with too much wing tip weight.

- People fly too nose heavy.

- People want to fly too slowly!!

- Most people's planes are too heavy.

- People “accept” an easy trim adjustment on their plane.

- People have a hard time “seeing” what their plane is doing.

- People are reluctant to try trim changes for fear of losing what they had.

- People are VERY reluctant to take a knife to their plane to fix it.

- Most people can score better than they do, because their planes' trim is holding them back.

- Most people don't know how to systematically approach the trimming process.

- I have heard too many times that someone's plane flew “right off the board.”. Really?

Starting with the first item, flying with too much tip weight is one of the most common problems in many planes. More than a decade ago I flew a plane that had just finished in the Top 5 of the Nats, and was appalled at how badly the plane hinged (dropped the outboard tip in corners) at even a “soft” corner. It was also very difficult to manage at the intersections of the consecutive eights. The point here is that this is so common that even a Top 5 pilot had this issue but was talented enough to work around it. I can't imagine how well he would have done if that issue was resolved! If a Top 5 pilot has this issue, it is easy for most to have this problem. Be very aware of this when you follow the trimming process.

The next issue is that too many pilots fly too nose heavy. Yes, it makes things feel nice and cozy, smooth and graceful, but too many over do this. It can increase the stick force too high and make the plane more difficult to fly in the wind. Partly for that reason, many choose not to fly in a good wind because they are concerned for the safety of their plane. And that can be for a very good reason. Be aware of this when trimming your plane.

Right behind this is the habit of wanting to fly too slowly. Yes, I know that it really looks cool when a real slow flight is executed perfectly. If I could fly consistently that way, I would. However this creates issues with flying in the wind. Many think that their reflexes can't take flying fast any more. I'm with you on that, IF the plane is out of trim. However, when in trim, flying fast is really not an issue. Reference a Skylark at VSC a few years ago that was flying at 4.2 seconds a lap. It really did NOT feel that fast, and was actually easy to fly. The slower you fly the plane, the more sensitive it will become to certain trim issues and make it feel like you need better reflexes. Work on the trim, and keep the speed up (relative to flying too slow).

Related to this is the fact that too many planes are simply too heavy! This extra weight forces you to fly faster to increase the dynamic pressure on the plane, thus giving more lift at the same angle of attack. It also increases the line tension, which many feel they like. Once again this issue creates issues with flying in poor conditions, like high winds or dead calm. It is easy to be fooled into thinking that a heavy plane really does fly well. I know as I have been there as well. Simply put, keep the weight under control to maximize your flight score. I'm not talking here about building a total feather, like Jason Greer's Impact at 56 ounces on electric, ready to fly, but keep the weight under control. More on that later!

I find that many pilots will accept an “easy” adjustment on their plane where a more complex combination will give better performance. My guess is that many don't know that things can be better, and think they have done a good thing. Well, they did do a good thing but now armed with this flow chart, they can find something better. Most experienced competition pilots will tell you that they stop trimming their plane with its last flight. It's a fact of life, so don't just accept a convenient trim.

I have also seen that many pilots can't see what their planes are doing wrong. This can range from the novice to the expert competition flier. This is when it is necessary to have a helper that can watch your plane and accurately communicate to you what is going on. It can also be beneficial to have an experienced pilot fly your plane to see what is wrong. At the same time, you can see your plane from a judges' perspective. The trick is to learn to see these fine points from the pilots' perspective, so you are in control of your planes trim. The only thing I can suggest is to spend some flights going through the motions of doing the pattern, but instead of total focus on the maneuver shapes and placement, spend that focus watching exactly what the plane is doing relative to the lines. Envision that there was a massless, infinitely rigid rod from your handle to the outboard tip of the plane. It is “easy” to envision what the rigid rod should be doing, but practice seeing what the plane is doing relative to the imaginary rod in local pitch, roll, and yaw. These excursions from the ideal position are a result of trim anomalies, and what they are doing tell you what trim is off. Try your best to envision this.

I can't tell you how many times I have heard that someone won't change things for fear of losing what they currently have. Somehow, if they can't mark where the current settings are that might be an issue, but measuring tip weight, marking LO position, marking the CG location, and measuring horn actuation points are not that hard to do. Mark or record all of these trim settings so if you change something and don't like it you can easily return to the previous setting. No excuses here!

I know many who refuse to take a knife to their plane to fix something that is wrong. I know as I have been there as well. It IS really hard to do that to your new pride and joy that you spent so much time making. You have to decide what is more important, a slightly higher appearance score or a much improved flight score. I was there in 2013 with my first Predator. I had to completely open the bottom of the plane to repair the control system due to a stooge mishap. It was repaired and still scored 19 appearance points a few months later at the Nats. If you have to cut into it, do it, but plan you work carefully.

After flying many other pilots' planes I find that there are a lot of pilots out there which could score better with some simple trim changes. This probably goes back to them not being able to “see” the trim anomalies. Fear not, if you think you should score better follow the flow chart to improve the trim of your plane, and your scores should go up as well!

I also find that most pilots don't have a thorough plan for finding their optimal trim. I trust that the flow chart presented resolves that issue.

Finally, how many pilots do you know who claimed that their plane flew “right off the board”? Yes, we all work hard to “bench trim” the new plane prior to flight, but I have NEVER had one fly totally without any adjustment. If you happen on one of these, I suspect you are in denial of reality. This procedure we have discussed for the last several months is what you would use to find that your pride and joy maybe isn't as perfect as you felt on those first few flights. I know because I have been guilty of that as well. Sometimes we just want our plane to be super and our overly positive attitude clouds our objective assessment of the plane. Be aware!

What is the point of these observations? If you find yourself in one or more of these “buckets”, take a truly objective assessment of it and then take steps to rectify the situation. This may involve extra work, but the result will be a better flying plane. If it doesn't need rectification, keep it in the back of your mind when making future adjustments. With time, you may find later that you really were in one of those buckets! An example would be that you fly nose heavy. Once you recognize this, try moving the CG aft “some” and fly it that way for a while. You might be surprised!

The following are some general guidelines for setting up your plane geometry and flight parameters. Setting up using these parameters will make the path through the flow chart easier as you will be closer to your desired trim at the start.

- The wing loading should not exceed 14 ounces per square foot. Yeah, that sounds heavy, and it is, but many competitive stunt planes fly near or above this point. For a 700 square inch plane, that about 68 ounces. Not light, but workable. If you are above this you will have problems in the dead calm and or strong winds.

- If you are using the same design for a second (or more) time(s), use the trim settings on the previous as a starting place…Unless it was a basket case. This is always a good plan, but variances in the build can cause subtle variations that will make a difference. For instance, did the flaps have EXACTLY the same torsional stiffness, as no two pieces of wood are the same? How about the stiffness of the elevators? These can cause a difference in response to control inputs, and may actually require a different flap to elevator ratio. Were the engine thrust line, wing centerline and the stab centerlines all exactly the same as the first plane? Point is there are many places where differences can occur and cause the plane to feel different. Nonetheless, starting where the last plane ended up is a good place to start with your next identical plane and can help streamline the trimming process.

- Start with the flaps at 1:1 unless the design calls for something different. This is one of the parameters I have spent a LOT of time working on to find an “optimum” geometry. In Bulgaria in 2012, my flaps moved 20% more than the elevators. That's just the opposite of what many do. A year later on the same plane, the elevators moved about 10% more than the flaps with a more forward CG. What is the point? I spent a lot of time messing with this and am not sure it scored any better either way. If you start a 1:1 (provided that's what the plans call for) set it there and try not to move it from there. It can save a lot of time with the flow chart adjustments.

- Start with the CG per the design, or set at about 80% of MAC for gas or 85% for electric. Like the flap to elevator ratio, much time can be spent fiddling with this parameter as well. The numbers quoted are a good ballpark place to start in your adjustments. However, when forced to try either changing the flap to elevator ratio OR the CG, move the CG first.

- Set leadouts at 3 to 4 degrees aft of CG. This again is based on years of flying and these numbers will get you close. For years I flew with fairly forward leadout positions, but have changed to a farther aft position. As mentioned previously, the farther aft the leadouts go the less the plane will wind-up in the wind. Of course, there are always limits to these settings!

- Shoot for 5.2 to 5.3 sec/lap to start with. This is generally for 70 foot lines. This allows the plane to have adequate speed to fly through maneuvers and not cause issues with lack of line tension, etc. As trim evolves, that can and will change.

- With electrics, leveling the wings is easier as you only need a 1-1/2-minute flight to verify. This is one of the bonuses of electrics, no wasted time getting the wings level. Step one of the flow chart can go much faster. The can relates to “tweaking” the flaps. That process is inexact at best, and problematic at worse. I developed a system that has a screw adjustment for the wing leveling, and step one might take three short flights with it. More on that feature in future articles. With “tweaking” the horn, I have seen it take nearly a day to get the wings level. There are other systems that have a segment of flap attached to a rod with a threaded rod. That system is also easy to adjust, but I have had issues with these in the past and won't use them anymore.

- If using electric set the engine to 2 degrees offset, and leave it there. This is a simple adjustment to make that has worked well for me. This was discussed previously, and all my planes now have this offset.

It still might seem intimidating to try to go through the chart and try every variable, and it can take a lot of time. However, there are some combinations of adjustments that shorten the process. They are as follows:

- Prop diameter and CG. These two are totally dependent on each other. If you increase the diameter, the CG will have to move aft to get a similar pitch response. Similar, but to a lesser degree, prop pitch works the same way. More pitch, more aft CG. The differences here are small, but do exist. Per the chart, you try one variable at a time, and you should. After some practice, you will find how much to move the CG for a given diameter. This will save time in the future.

- Flap to elevator ratio and plane weight. We talked earlier about these ratios. If you plane comes in at all on the heavy side, do NOT consider moving the elevators more than the flaps. Only with very light planes would you consider more elevator than flap. The issue here is that as the weight goes up so does the need for lift, and more flap deflection will provide that, up to a certain point! Too much flap deflection and then flow separation occurs near the flap hinge line and bad things happen then. This magical point when flow separation occurs will vary based on your design and weight. Check out Igor's article on the MaxBee! The savings here is that you should not try everything on the chart based on the knowledge of its weight.

- LO position and “Wind up” in the wind. Since using electrics, this phenomenon has become much easier to detect. With constant power settings available, it is clear that with a more forward CG the plane flies “cleaner” with less drag. As a result when the wind “pushes” on the plane and adds energy to it, there is less resistance to keep it from speeding up, and speed up it does, even with the constant speed systems. I thought I might have felt this with IC engines, but was not sure the engine was not the culprit. The point here is that if you notice the plane speeding up in consecutive maneuvers and it is NOT the motor doing this, consider moving the leadouts aft and try again.

- LO position and tip weight. These two are “twin brothers.” You can't change one without the other. PERIOD. Move the leadouts forward and you will need more tip weight. Likewise, moving then aft requires less. By moving the leadouts without changing the tip weight, you will notice that the plane either hinges out or in based on the change. Move the leadouts a fixed amount and rebalance the tip weight, and record that data. Next time you will have a much better idea of how much tip weight needs to change when you move the leadouts.

- Prop diameter and Overhead Line tension. In general, the more prop diameter you have, the better the overhead line tension will be. This is sometimes hard to determine with certainty, as most times when a larger diameter prop is used it also will have a different shape. It also will use a different part of the engine's torque curve and respond differently. It sometimes becomes a chicken and the egg question. However, in general, it will provide better overhead performance.

If you look carefully at the flow chart you will notice that the elevator to flap ratio shows up in many of the criteria. By selecting a setting and leaving it fixed in one position, it makes the process much shorter to go through. This then forces the CG to be adjusted to balance the squares and the corners. Once the CG is chosen, then the number of variables is not too significant. This assumes that you are starting with a “good” ratio between the two. The guidelines above should help that. This is in general the process I go through. I will select a variable to leave fixed and then optimize the others. At some point, I consider changing the original variable I fixed, and move forward with the process again.

This concludes the discussion on the flow chart. My goal was to make the process that I use available to anyone who would want to use it. There are also guidelines and simplifications that can be made to simplify the process and they have also been discussed. If you have questions on any of this, you can e-mail me a question on it.

Until next time, keep the flow chart in your back pocket!.

The Trim Flow Chart

Trim Flow Chart Chapter 1: Basic trim

Trim Flow Chart Chapter 2: Advanced trim

Trim Flow Chart Chapter 3: Criteria problems

Trim Flow Chart Chapter 4: Turning and tracking the same

Trim Flow Chart Chapter 5: Advanced trim Part 1

Trim Flow Chart Chapter 6: Advanced Trim Part 2

Back to Aerobatics section

Back to Walker on Stunt index page

Flying Lines home page

This page was upated Oct. 23, 2015